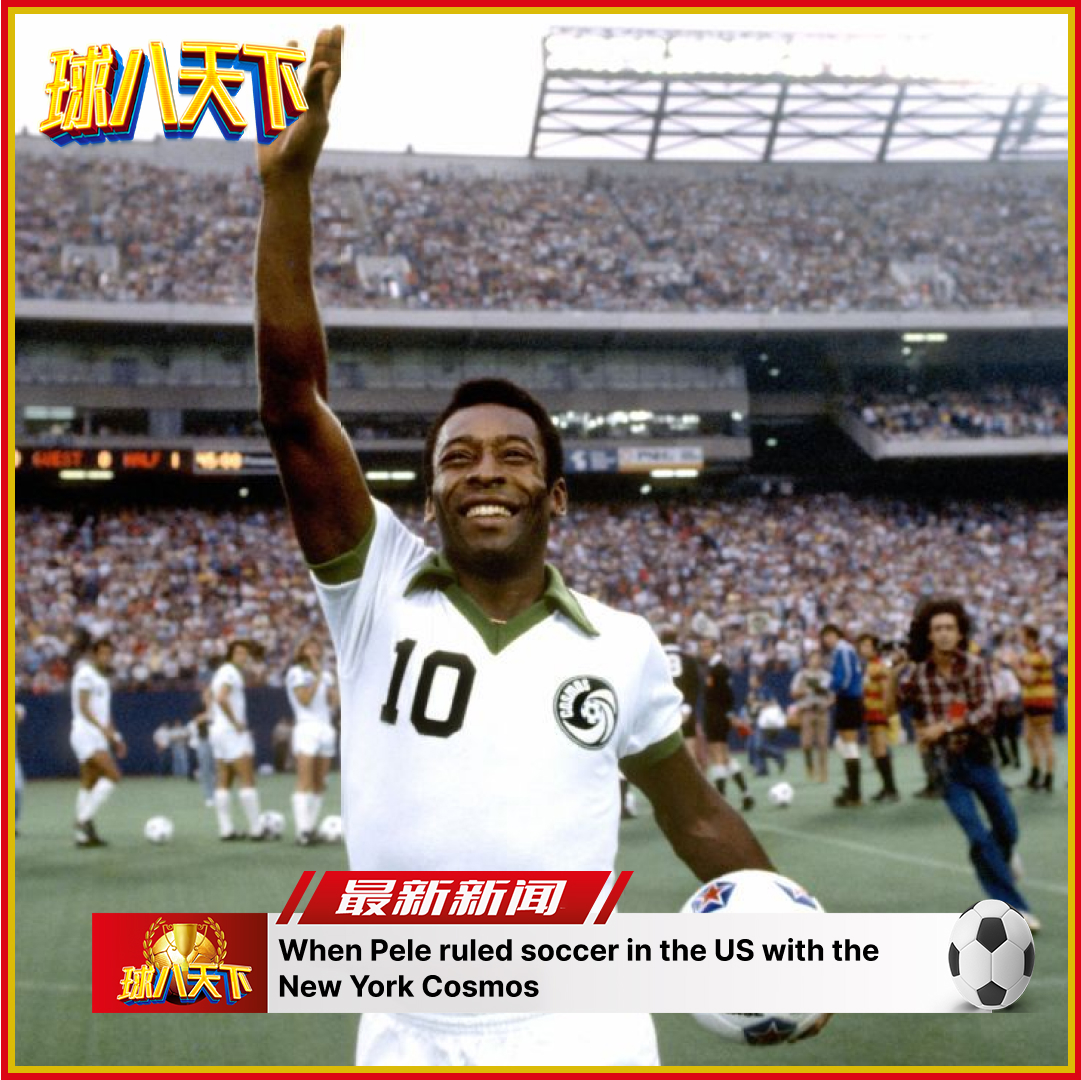

When Pele ruled soccer in the US with the New York Cosmos

On the morning of June 11, 1975, a pack of rubbernecking New Yorkers gathers on West 52nd Street. They’re standing outside the venerable “21” club, a former speakeasy turned posh canteen to presidents, plutocrats and Hollywood grandees, drawn there by the steady drone of a police helicopter overhead — and, no doubt, by the conspicuous gaggle of bulky gentlemen in telltale dark suits, sunglasses and coiled wire earpieces monitoring the entrance.

As some onlookers speculate about the identity of the eminence du jour — Frank Sinatra? Jackie O? Elizabeth Taylor? — inside “21,” a mosh pit of 200-plus reporters, cameramen and photographers waits impatiently for something to happen. They’re all crammed into an upstairs space called the Hunt Room, an homage to the massive elk and antelope antlers that are stuffed and mounted on the oak-paneled walls. All they know is that a news conference will be starting at 11 a.m.

Except it doesn’t. The mystery guest is, so far, 20 minutes late. But then Pele is always late. The man, who is all whirring feet and pumping legs on a soccer field, downshifts to “leisurely” when off it.

His job on this day is simply to show up and ceremoniously sign his name to a $4.75 million, three-year contract with the Warner Communications-owned soccer club, the New York Cosmos, that will make him the highest-paid player in the firmament. Anyone else in this enviable position might experience an adrenaline rush and pick up the pace — anyone but the mellow 34-year-old Brazilian.

By 11:35, Warner executives, cognizant of the toxic mood building in the Hunt Room, try to calm things down by assigning a PR guy to announce that “Pele is just on his way now” while whispering among themselves: “Where the hell is he?”

As it happens, he is still in his hotel room huddling with lawyers, who’ve found a last-minute snag in the contract. Pele, arguably the greatest soccer player in the sport’s history, doesn’t want to be identified as a soccer player, period: it’s the only way to avoid messy tax issues with the Brazilian government. Lest they risk losing him, Warner has to resolve the problem, and quickly, so it comes up with an ingenious plan: Atlantic Records, a Warner subsidiary, would list Pele as a “recording artist” for the label. (It isn’t that much of a stretch: Pele, an avid guitarist, already has two solid-gold hits in Brazil to his credit, and his friend Sergio Mendes had recently asked him to do a record together.)

Back in the Hunt Room, tensions steadily escalate as the minutes pass. Film crews and reporters shove and elbow each other for prime positions near the podium, their voices rising along with their tempers. Cosmos general manager Clive Toye, a well-tailored and normally well-mannered Brit, is all but screaming, “Gentlemen of the press! GENTLEMEN OF THE PRESS! Please behave yourselves!”

Toye, after all, spent three years pursuing Pele around the world in one of the great corporate chases of all time, logging 30,000 air miles, racking up $8,000 a month in phone bills, and finally having to solicit a telegram from U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger to his Brazilian counterpart imploring the latter to allow Pele, deemed an “unexportable national treasure,” to play for the Cosmos. At this point, Toye wasn’t about to let his long-sought prize get manhandled by some rowdy journos.

Meanwhile, outside “21,” a compactly built man steps out of a black limousine, dressed in a black brocade leisure suit with a red Big Apple pinned to the lapel. Security guards shield him as he moves from the car into the club. It is now 12:15, but despite arriving 75 minutes later than scheduled, Pele is still in no hurry; he stops at the restaurant’s kitchen to autograph a menu for the chef and shake hands with the mostly Latin American staff.

At last, he enters the Hunt Room, unnoticed amid the chaos: a brawl has broken out between two photographers jockeying for the same perch. Bodies are tumbling over tables and you can hear the brittle crunch of glasses shattering beneath someone’s foot. It is a mini-riot — over soccer, of all things — and it is happening in midtown Manhattan! Yet Pele remains eerily tranquil as he makes his way to the podium and stands there, smiling shyly, hands raised in the familiar “V” salute. Slowly the media horde becomes aware of the great man’s presence among them, and the pandemonium dies down. Brandishing a silver pen, Pele signs the newly revised contract.

Then he puts the pen down and faces the packed room, grinning widely. “Now you can say to the world,” Pele tells the suddenly hushed audience, “soccer has finally arrived in the United States.”

Pele came to America at a time when baseball’s once unchallenged hold on the popular imagination was slipping away and the soccer-phobes in the media were panicking that that yet another sport — a foreign one, no less! — had arrived to further erode its hegemony.

Just a couple of years earlier, fresh out of college, I took a job at the New York Daily News hoping to kick-start my journalistic career. Having grown up in a soccer-mad European family and played the sport in college, I naturally inquired about covering the Cosmos as a regular beat. Dick Young, the paper’s crusty, nationally syndicated sports columnist, put his arm around my shoulder and looked me square in my guileless face. “Don’t waste your time on soccer, kid,” he said. “It’s a game for commie pansies.”

It was also a game fans avoided in droves. When the Cosmos won the North American Soccer League title in 1972, the attendance was announced at 6,000, a number which failed to take into account that at least half of those in attendance had been given free tickets with their purchase of a Burger King Double Whopper. When I broke the news of Pele signing with the Cosmos, it was splashed across the back page, the first time a soccer story had appeared anywhere in the paper other than buried next to the hair replacement ads. If American soccer had been transformed overnight, so had I. No longer was I at the bottom of the sporting food chain, but rather the envy of my colleagues. Since I had access to the biggest sports star in the world I was even being interviewed by other American journalists who wanted to know more about this fellow “Peeley.”

Best of all, I had a book contract to collaborate with Pele on a memoir about his magical mystery tour of American soccer. For the next two years, I shadowed him as he crisscrossed the country on a self-declared mission to bring the beautiful game to the last outpost on earth seemingly indifferent to its charms. We spoke on airplanes, in limos, hotels and locker rooms, at his lavish Sutton Place apartment and his sprawling Hamptons estate. I even hung out with him at the notorious disco, Studio 54, until a burly, bullet-headed bouncer threw me out.

In the course of my time with him, I came to know all the different Peles: Pele the Deity, Pele the Brand, Pele the Soccer Evangelist, Pele the Family Man and Pele the Party Animal. All were generous to a fault, unfailingly polite, surprisingly droll and — did I mention — always late?

Pele possessed an innate sweetness that was evident whenever you were in his presence. “How are you, my friend?” was his go-to greeting, whether he was meeting you for the first time or running into you at an airport decades later. I once asked him if he uttered those words to everyone he encountered. “Not everyone,” he replied impishly. “That would be about half the people in the world.”

Though Pele was regularly feted by the high and mighty — from heads of church and state to corporate billionaires — he never lost his sense of boyish wonder. The key to his success and longevity, he maintained, was to “stay as a child who loves the game.” In the end, he was essentially a private man — as private as the most famous person on the planet could be.